The Ultimate Guide to Drinking Sake in Japan (2024 Edition)

Those visiting Japan will no doubt want to try sake, its national alcoholic beverage. But with an ancient history and overwhelming number of varieties, it can be difficult for beginners to enjoy sake in Japan. In this article, we’ll tell you everything you need to know about how to drink sake, including the types of sake, how to read sake bottles, how to best prepare and store sake, and more. So, before jumping in and risking a bottle that doesn’t suit your taste, read this Japanese sake guide to ensure you’re experiencing sake culture the right way!

This post may contain affiliate links. If you buy through them, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

Types of Japanese Sake

Similar to most alcoholic beverages, sake has a massive range. Different brewing techniques yield a staggering variety of unique flavors and styles. While this can feel a little overwhelming, start your sake journey with baby steps by familiarizing yourself with the popular sake below.

Seishu (清酒)

If you’ve ever tried sake before, it was likely seishu. Clear, crisp, and fresh, it can be both sweet and dry. Meaning “refined sake,” seishu is a base from which more complex sake is launched. It is fermented, filtered, pasteurized, and diluted, balancing the alcohol content and mellowing the flavor. It’s the go-to sake at any liquor shop across Japan. Its price depends upon several factors, particularly the milling of rice, and can range significantly. The cheapest is known as futsushu (普通酒) and is commonly sold in a paper carton.

Honjozo (本醸造)

Honjozo is a seishu delicately brewed with an emphasis on flavor. It boasts a polishing ratio, or seimai buai (精米歩合), of 70% or lower, making it of a higher quality than futsushu. While a “polishing ratio” may sound like a head-scratcher, it simply refers to the level of rice milling. Rice’s starchy core is the key to good sake, making it necessary for all brewing rice to be milled to some degree. A 70% polishing ratio means that at least 30% of the grain’s surface is removed, leaving the remaining 70% to be brewed. Tokubetsu honjozo (特別本醸造), with a polishing ratio of 60% or less, is also available.

Ginjo (吟醸)

A premium sake with a polishing ratio of 60% or less, ginjo is known for its rich, fruity fragrance called ginjo-ka (吟醸香). Try drinking it in a wine glass to amplify these mouthwatering aromas!

Daiginjo (大吟醸)

The crème de la crème of nihonshu, daiginjo flaunts a polishing ratio of at least 50%. The daiginjo brew is the pride of most breweries, often being the most expensive and limited offering. Light, fragrant, and with a fuller body than ginjo, it is a treat to be savored!

Junmai (純米)

Pure rice junmai sake is created without brewer’s alcohol, which is added to most seishu for extra flavor. Junmai is sake at its purest – nothing but water, rice, and the koji fermentation bacteria. Junmai is dry, flavorsome, and packs an acidic kick. Junmai ginjo and daiginjo sakes are also available.

Namazake (生酒)

Namazake is completely unpasteurized, giving it a fresh, tingly punch with a fruity undertone. Being unpasteurized, it has not been heated to kill off the fermentation bacteria. This means it can go off easily, so always keep it cool and don’t store it for too long! Being relatively easy to drink, namazake is great for beginners! It usually appears around spring and summer.

Genshu (原酒)

Undiluted with water, genshu’s full-bodied punch and higher alcohol content is perfect for those who can hold their drink! While normal sake typically has an alcohol content of around 15%, genshu typically contains closer to 20% and can even be enjoyed on the rocks.

Cloudy

An aesthetically-pleasing sake with a milky texture and sweet thickness, cloudy sake is unfiltered, allowing tiny pieces of fermented rice to remain within the bottle. There are two main types: the completely unfiltered doburoku (どぶろく) and the partially filtered nigorizake (濁り酒). Another good choice for beginners!

And Much More!

While the above may seem like a lot, it’s still just sake 101! Once you feel comfortable enough, aged koshu sakes, hand-mashed kimoto sakes, and seasonal sakes like autumn’s hiyaoroshi are waiting to be discovered.

Our Top Tips

JR Pass for Whole Japan

Explore Japan in the most convenient and economical way with a Japan Rail Pass! It is valid for the majority of railways and local buses operated by JR.

Sake Buying Guide

tarin chiarakul / Shutterstock.com

Even if you know the jargon, actually finding the sake you’re after is a whole other thing. Sake bottles, notorious for calligraphy of difficult kanji, are intimidating to say the least! But fear not, everything you need to know about sake can be easily discovered from the bottle with just a few pointers.

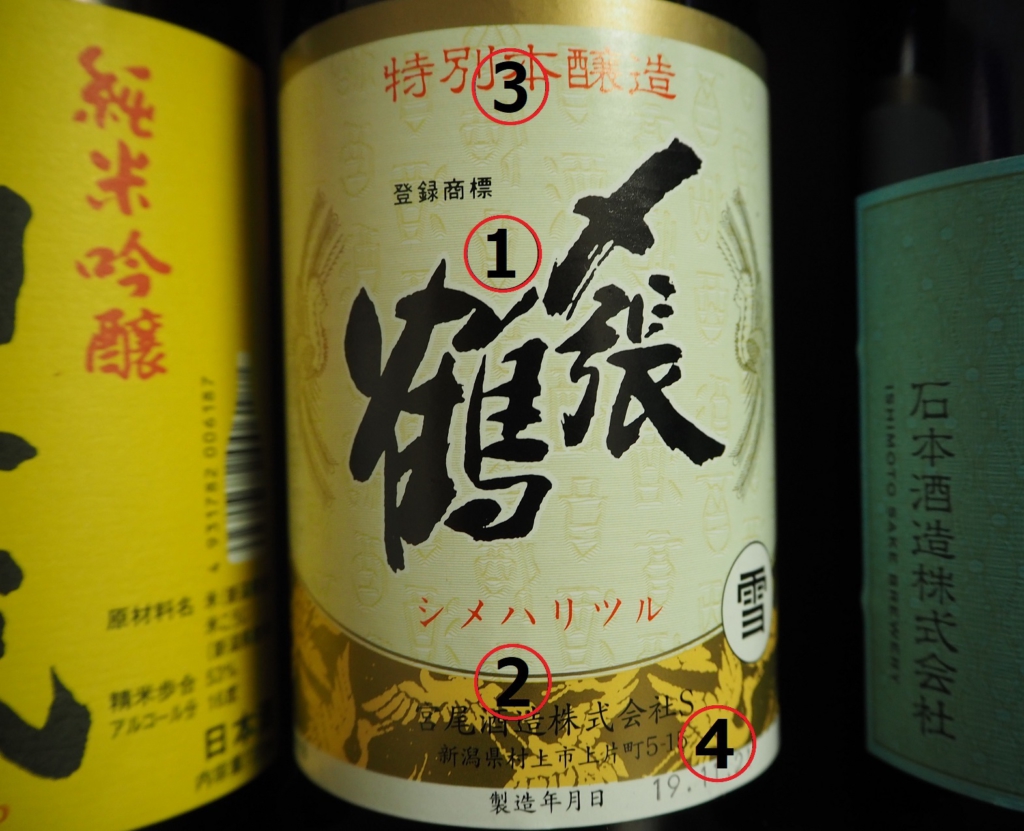

Reading the Label on a Sake Bottle

Let’s look at a standard bottle. This is from the renowned brewery Shime-haritsuru in Niigata. Follow each number to its corresponding explanation. Keep in mind that not all sake bottles look the same, and your experience may vary!

1. The name of the sake. While some swanky breweries have started experimenting with romaji lettering, you can generally expect kanji.

2. The name and address of the brewery. Not so important unless you’re a fan of a certain brewery or region, however, you might want to keep this in mind as you learn more about sake. Since sake is made from water and rice, the quality of these base ingredients is what decides the flavor and quality of the drink. Hence famous rice-producing prefectures or areas famous for their natural water often produce the best sake.

3. The make of the sake. It will likely be from the above list. This particular sake is a “tokubetsu honjozo.” It will probably be dry and light and pair well with Japanese food. This information reveals the most about what kind of sake you’re about to drink.

4. The bottling date. Be wary if it’s more than a year old.

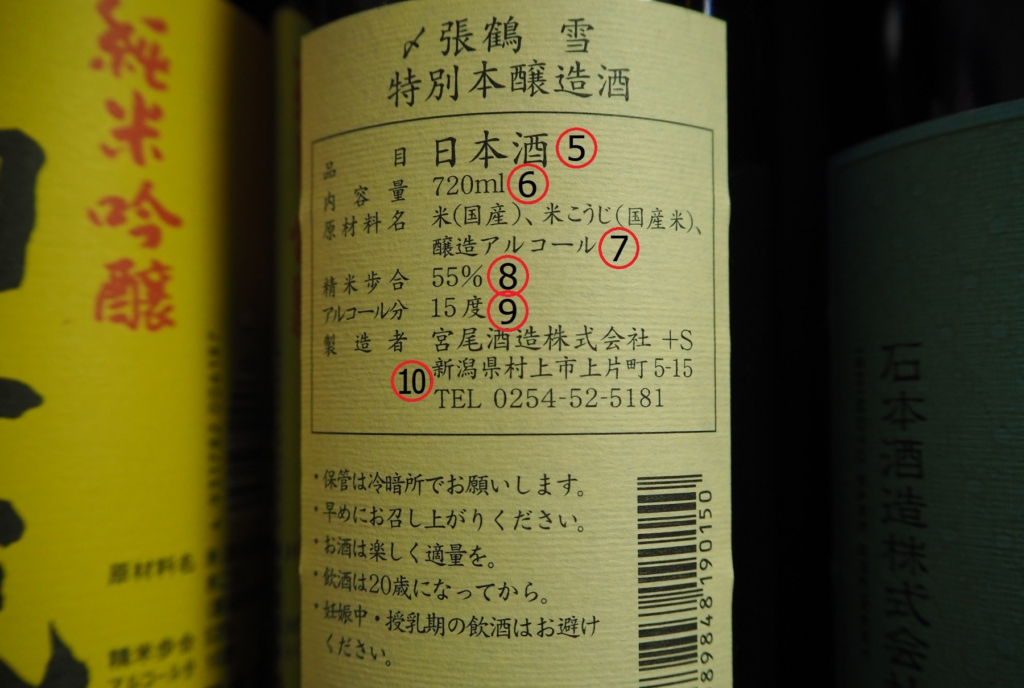

5. The type of alcohol. It should say 日本酒 (nihonshu). Shochu (焼酎) bottles appear very similar to nihonshu, so don’t buy the wrong drink!

6. The net content. Sake is generally sold in three different sizes: 1800ml bottles, called “issho bin” (一升瓶); 720ml bottles, called “shi-go bin” (四合瓶); or 300ml bottles.

7. The base ingredients – in this case, rice (米), kome koji (米麹, malted rice), and brewer’s alcohol (製造アルコール).

8. The rice polishing ratio.

9. The alcohol content. Will usually be between 14% and 20%.

10. The address of the brewery.

Inside a Liquor Shop

Pack-Shot / Shutterstock.com

Japanese liquor shops have no universal sake presentation. They generally order by price, ranging from dirt-cheap futsushu paper cartons to daiginjo glass bottles. However, this may not always be the case. If you can’t find something, use the terminology you’ve learned here and ask the staff!

What Should I Buy?

Dummy Origami / Shutterstock.com

Beginners should start with sweet amakuchi (甘口) sake, a sake with a similar acidity to white wine. Just as you wouldn’t give a first-time wine drinker a swig of unpleasant box wine, higher-quality ginjo and daiginjo sakes are a better introduction than most cheap futsushu.

Nigori and namazakes are also well-loved by even those who can’t stand sake, so they can be a good jumping-off point, too! Avoid dry karakuchi (辛口) for your first bottle. As you get used to sake, you’ll likely find yourself growing partial to drier flavors down the line, but it can be a bit harsh for a first-time sake drinker.

How to Drink Sake

A “tokkuri” (sake pitcher) and set of “ochoko” (small sake cups)

So, you’ve got your sake! Well done! Time to enjoy the fruits of your labor and try a glass! But before you do, to get the most out of your sake, you’ll need to put in a little more work!

Get the Gear

Coming in all shapes, sizes, colors, and materials, you can express yourself through the creative craftsmanship of ochoko (sake cups) and tokkuri (sake pitchers). If you’re partial to cold sake, opt for a smaller ochoko made from porcelain, metal, or glass.

For hot sake, avoid glass and metal and stick with porcelain or ceramic. If an ochoko isn’t your thing, wine glasses are becoming increasingly accepted in the nihonshu world, so don’t be ashamed if you don’t buy an ochoko at all!

Prepare the Sake

How to Drink Cold Sake

If you want your sake chilled, place the bottle in the fridge for an hour or so prior to drinking. You can also pour your desired amount into a tokkuri and chill that instead.

How to Make Hot Sake

For hot sake, submerge your tokkuri in boiled water for several minutes. This should yield a nice warm sake ready to drink straight away! Do not continue boiling the water while your tokkuri is submerged, but feel free to experiment with different temperatures by leaving it in for longer!

Room Temperature Sake

Of course, room temperature sake is completely acceptable, and in some cases better, so indulging as soon as you arrive home is perfectly fine! Different sakes have varying optimal temperatures, with honjozo often being warmed while daiginjo served chilled. Ask the store staff for their recommended drinking style during your purchase.

Enjoy!

Sake is all about enjoyment, so if you have a unique way to drink sake, by all means, be free! However, for your first drink, we recommend sipping slowly while making mental notes of taste and fragrance. Don’t dilute with water or mix with anything else – sake is to be relished on its own! It’s important to eat and drink water with sake, so prepare some otsumami and keep hydrated. Sake is notorious for brutal next-day hangovers, so don’t go overboard!

lrosebrugh / Shutterstock.com

Sake Terminology

Ochoko (御猪口/おちょこ): Sake cup

Tokkuri (徳利): Sake pitcher

Kan (燗): Warm sake

Hiya (冷): Chilled sake

Jou-on (常温): Room temperature

Shi-go bin (四合瓶): 720ml bottle

Issho bin (一升瓶): 1800ml bottle

Shi-in (試飲): Tasting (any drink)

Kikizake (利き酒): Sake tasting

Amakuchi (甘口): Sweet

Karakuchi (辛口): Dry

Umami (旨み): Savory flavors often found in sake

Jizake (地酒): Local sake

Sakagura (酒蔵): Sake brewery

Jouzo (醸造): Brewing

Shuzou (酒造): Sake (alcohol) brewing

The information in this article is accurate at the time of publication.